Like A Daydream, Or A Fever

They were sunset days, languid days, firefly days, monotonous days, porch-light days, haunted days, sweat-soaked days, tortuous days, dry-thunder days, mosquito days, days that stunk of pot smoke and stale beer, days butchered and dissected, days stretching asymptotically towards forever. We swam inside the warm guts of the briefest eternity. We were fifteen and already world-weary, traversing new landscapes of boredom.

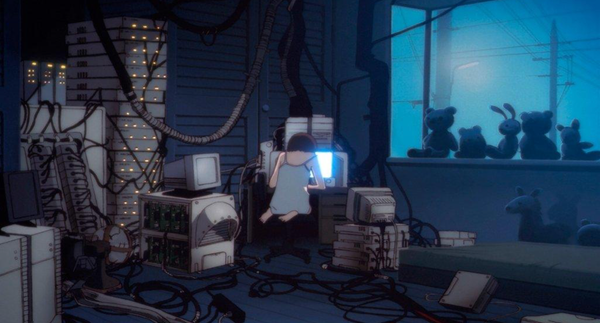

I was a fuckup on some ontological register. I was barely a teenager and already I’d proven myself uniquely unsuited for everything I’d ever tried. I’d been in Boy Scouts, Little League Baseball (go Voles), Youth Soccer, Karate, and an extremely brief stint in Debate. I have a crystal-clear memory of myself at eight, lying in the outfield, watching a line drive tear through the cloudless sky above my head. Eventually my parents gave up on attempting to mold me into a fine and upstanding young man and left me to my own devices. I figured I’d end up like Connor, who wrote me letters from the base in Korea where he was stationed. I never figured I’d be much good as a soldier. I never figured I’d be much good at anything. I liked Coheed and Cambria and Dune and Neon Genesis Evangelion and everything else more or less scared the shit out of me.

I met Mara in middle school. One day she showed up to Mr. Czenowitz’s fourth period Science class with hair the color of one of those Atomic Fireball candies, the kind they sold at the diner by the pharmacy where Mom got her meds filled. I sat a few seats behind her, trying not to stare, failing, staring anyway. I had never noticed her before. Halfway through the class something wet and maggoty appeared on the back of her neck. I watched her turn to make eye contact with Christine Vernon, who spun a straw between her fingers nonchalantly. Christine wore an expression I had just begun to think of as ‘shit-eating.’

Christine said:

“Dyke.”

If I had been a stronger person, the boy my parents raised me to be, the person I had been told to be in the Upstander-Not-Bystander presentations we had received ever since an upperclassman ran a hose from his car exhaust and left the engine running in the high school parking lot, I would have said something. Instead I just watched, and felt the guilt bore through my gut like acid.

Later I found her outside. She was squatting by one of the disused storage sheds by the fences that marked the edge of the school property. I scuffed my sneakers against the mud, uncertain.

“I saw what happened back there,” I said. “With Christine.”

She didn’t say anything for a moment. I was arrested by her gaze. Her eyes were big and brown and almost more fit for an animal than a human being. I had always preferred animals, anyway.

“It wasn’t cool for her to call you that,” I said.

“It’s okay,” she said. “Thanks.”

She pointed to my backpack. “Is that Cloud’s?”

I fumbled for a moment before shifting it enough that the model keychain of Cloud Strife’s Buster Sword was visible. “Oh. Uh, yeah.”

“That’s cool,” she said. She nodded, sniffed. “Cloud’s cool.”

And that was that.

To say she was my best friend was correct and insufficient. Mara was the only person in whose presence I felt substantial. Around others I contorted myself to every shift in mood, shoved this way and that like a windblown ghost. She was my closest friend and only confidant. We carried each other through sprained wrists and scraped ankles and rages and heartbreaks and all the little tragedies of childhood. With her I felt like I was standing on the precipice of some other, brighter universe.

The night she came out we were wine-drunk off a bottle of pinot she’d stolen from her mom. We were sitting in the living room, throwing back sippy-cup glasses. The TV was playing the scene from Ginger Snaps where Ginger and Brigitte hide Trina’s body in a freezer. The room was dark, the house empty, Mara’s parents absent on some something-or-other. Outside a police car wailed past, careening into the dark. She held herself ramrod-straight, the lights of the screen dancing over the planes of her face. She said nothing. In that moment I was struck dumb by her beauty: less the beauty of a human being and more the beauty of a sunset, a whale breaching, something sacred and inhuman and extremely far away.

I didn’t say anything when she told me. All my words seemed leaden. She put her head on my lap. I ran my fingers through her hair while she wept. I felt the wrack running through her. I felt her ragged, labored breathing. I whispered: it’s okay. It’s okay. I felt swollen with love; overflowing. Golden light streamed out of my every pore. I couldn’t express the joy I felt at this moment, as if Mara had taken my hand and shown me a glimpse of the other side of life.

I think she knew I loved her. I never said it– it would be an embarrassment to us both. I was too damaged to do the whole boy-girl thing, even if Mara had been interested in boys in the first place. I never wanted anything more than what we had. Everything unstated could remain inviolable. We found our stasis and nestled there. We built a home for ourselves. I was quietly, invisibly, deliriously happy.

I can’t remember where I first heard about the ghost. There are certain things you just know as a kid, without being able to trace an origin, like how you can summon Bloody Mary by saying her name three times into a darkened mirror or how you’re supposed to hold your breath when you drive past a graveyard. It bubbled up over that summer, and pretty soon everyone had a story about it, although most were second or third hand.

No one could agree on whose ghost, exactly, it was. Luis Rios said it was the ghost of a suicide, who drowned herself after her boyfriend died in Vietnam. Juniper Holzer claimed it was an outlaw from the Old West, who died in a last stand with the police after burying a hoard of stolen gold. Rory Vartanian said it wasn’t a ghost at all, but a projection from an alien spacecraft, which was monitoring our town as part of some generations-long interstellar experiment. The only thing that people seemed to agree on was that the ghost made itself known at the wetlands at the edge of town, and that you were most likely to catch it at sunrise and sunset.

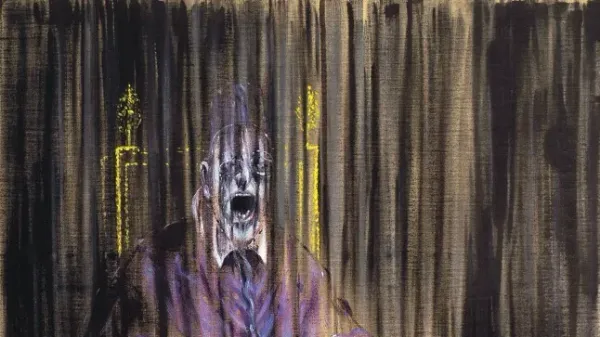

I didn’t know if I believed in ghosts. I didn’t know if I believed in anything, really. My family was Catholic in the vaguest sense– baptism, confirmation, services at Easter and Christmas, Mass maybe a handful of times a year. I sang the hymns and took Communion and listened to the services and felt nothing beyond the mundane. I had never felt the holy spirit move within me. I looked deep inside myself and found instead an absence, a hollow place where God was supposed to live. At fifteen that absence had crystallized; it felt as if I were carrying around some foreign organ, some emptiness colonizing every part of myself. Ghosts, at least, seemed more plausible than God or Satan: pure good and pure evil had little stake in my life. I thought if ghosts existed they must have been terribly lonely.

I succumbed out of sheer boredom. It was summer, and had been for long enough that the novelty of being out from school had been replaced by the sucking tedium of unstructured days. I mostly spent my time in Mara’s house, while her sister was working as a camp counselor and her parents were at work. I liked the smell of her house: unfamiliar yet comforting. I didn’t spend much time at home if I could help it. There were moments, alone in my room, where I felt as if I were being crushed beneath a thousand tons of water.

I didn’t hear her the first time she mentioned the ghost. She had to repeat it. I was sprawled on the carpet, heat-addled, languid and lazy. On the TV the Mario Kart: Double Dash main menu theme repeated ad infinitum.

“Why a ghost?”

I propped myself up on my elbows and looked at her. She was lying on the couch, laptop open across her knees. A few years of puberty seemed almost to have sharpened her, clarified everything already latent within. I was envious— for my part, the exact opposite seemed true. She shrugged, the motion rolling seamlessly across her body.

“‘Cause it’s a ghost. Wouldn’t you want to see one?”

I thought about it for a moment. I didn’t exactly know. As a kid I’d read fantasy stories about boys pulled into mystic fairylands, or exposed to wondrous supernatural otherworlds. At the end of the stories, the boys were always sent back home, to the dull, mundane lives they’d hated. Seeing a ghost would be like that, I thought. How could you go back to living a normal life, after having witnessed the secret world?

“I guess,” I said. “But it’s probably nothing, anyway. People like to bullshit.”

“There’s like a ninety percent chance it’s made up,” she agreed. “But that means there's a ten percent chance it’s real. And I’m dying here. I am sooooo bored.” She slumped into the couch to emphasize her point. “Also, we have to leave in a bit anyway. I’m picking up weed.”

I made a big show of considering it, having already mentally acquiesced as soon as she raised the idea. I followed wherever she went. I wanted to dwell in her slipstream. “Fine.”

We went out into the sweat-drowned afternoon. The sun, having reached its zenith, listed westward, slipping towards oblivion. Above the rows of near-identical houses a few wispy clouds ambled aimlessly across the sky. We rolled our bikes down the driveway and started to pedal, heading west.

The town flickered by. We rode down wide, empty, sunbaked roads, our bodies traversed by brief patches of shade. Trucks with Thin Blue Line decals sat vacant in driveways and garages. Day-drinking suburban dads in lawn chairs idly watched us as we passed, cracking beer cans, seeing nothing. We crossed beneath the shadows of skinny trees, all their branches angled skyward, as if our town was something foul they were withdrawing from. Mara caught an incline and pulled ahead. Her bike was Barbie pink, a gift for her eleventh birthday, when her parents still figured her tomboy phase was a fever soon to break. At fifteen the bike was rapidly becoming too small for her, but she still resolutely kept it around anyway as a kind of ironic joke.

After a few minutes she wrenched her bike sideways and stepped off. I coasted to a stop beside her. We pulled to a stop at a tiny island of trees set in the dead center of an intersection, a meager concession to public safety built after a buzzed driver t-boned a family of four a decade prior. She hopped her bike over the concrete curb and pulled it onto the sickly grass. I followed, grateful for the cool of the shade.

“Too fuckin’ hot,” she said. I wordlessly concurred by swiping away the beads of sweat that had collected in my eyebrows. “I want a Slurp-ee. And you’re paying.”

“Why me?”

“Because I’m buying the weed. Now, are we going or what?”

A break northward. Whitewashed houses and jagged fencing gave way to pharmacies and liquor stores, car dealerships and smoke shops, a hospital, a cemetery. The dojo where I had taken karate was long-gone, a nail salon standing in its place. There was something unsettling, I thought, about the fact that the places in which you’d spent your life could up and vanish. Gradually I was becoming a stranger to everywhere.

A man was lying against one of the walls of the 7-Eleven, eyes closed, his body surrounded by a puddle of something dark. I told myself that he was asleep and didn’t check. Inside the store the atmosphere was sterile and comfortingly nonspecific. That was the thing I liked about chains: go inside one of them and you could imagine yourself anywhere. A bored cashier with a metal bar inserted through the bridge of his nose watched us work the machine, listening to the dull mechanical grinding of its internals as it spat blue raspberry slush into our cups. The drinks were saccharine, aggressively chemical, disgusting. I finished the whole thing. We sat on the curb while Mara drained the last sludgy dregs of her own, watching the cars roar past. The tips of her fingers were stained blue. I caught myself staring, and a needle of self-loathing buried itself in my gut.

“If the ghost is real,” I said, “what do you think it’s doing there?”

“What do you mean, doing?”

I shrugged. “In movies ghosts always have something they’re supposed to do before they disappear. Unfinished business.”

Mara idly crushed the cup in her palm, rolling it between her hands. Above us, the sun was gradually inching lower. Shadows stretched like melting taffy.

“Maybe it’s waiting for something.”

“Like what?”

“I dunno.” She smiled big. There was blue dye between her teeth. “The same thing everyone else is, I guess.”

On the way back something caught Mara’s eye. She veered left, into a mostly-empty parking lot bordered on three sides by a strip mall. I heard her curse and sped up to follow. A few moving trucks were parked in front of a vacant lot like piranhas feeding off a corpse. Two men in coveralls hoisted a disconnected arcade machine into the belly of one of the vans. The signs had all been taken down, but you could still read EMPIRE ARCADE in the outlines of dust and grime left on the facade. An empty styrofoam cup scudded across the tarmac, turning end-over-end as it was caught in little eddies of wind.

“No,” Mara said. “No. Fuck, no.”

We stood there, watching the world empty out. Through the window you could see men peeling away squares of black carpeting adorned with neon squiggles, leaving behind bare stone. I remembered birthdays, after-school trips, long hours spent wandering between the corridors of glowing machines. I closed my eyes and tried to call up the giddy clamor of the arcade in full swing. It was the smell that came back the strongest: slightly damp, pungent with adolescent sweat. When I opened them again it was difficult to transpose my impressions of that time onto the building before me: it all seemed to have taken place in a different universe altogether.

“I had my eleventh birthday here,” Mara said. Her voice was very quiet. “They gave me a little paper crown. Mom got an ice cream cake with a picture of Sailor Moon on it. I ate too much and got nauseous in the car on the way back. I remember…”

I didn’t say anything. All my brain could conjure at that moment were cliches: dumb nonsense-phrases like everything happens for a reason or it’ll all be okay in the end. They were lies. Sometimes awful things just happened. Some days you woke up and everything was different forever. I felt vertiginous, as if I were standing on a ledge looking out over a bottomless drop.

She got on her bike and pedaled away without saying anything. I followed after. She stopped at a gutter by the side of the road, a muddy divot a few feet wide bracketed by cars on one side and an uneven wooden fence abutting a row of suburban houses on the other. Water had pooled in the depressions within the mud, their reflection forming little patches of captured sky. When I approached her she turned, and I saw that she was crying. For a moment I felt afraid. Fury and pain intermingled on her face.

I stood beside her, uncertain. I put my hands in my pockets and then I took them out again. I thought: I should say something. I didn’t. I counted cars. I thought about how many lives intersected our own for only an instant, how many drivers would pass through this town for a few brief minutes and never return.

“They’re fighting again,” she said. I watched her. Her gaze didn’t leave the road. I wondered what she was seeing, where she had gone behind her eyes. “A few times a week now. It gets better or worse, but…” She sniffed. She turned her hands outwards, as if she was placating someone. I knew Mara’s parents in only the vaguest of terms. The few times they’d met me I had sensed a subsumed hostility, as if their cordiality was a performance carried out only for my benefit.

“It’s worse,” she said. “Half the reason Jennifer’s at camp is to avoid their shit. And the thing with the Empire, it just…”

She trailed off. She balled her hands into fists and pressed them against the wood of the fencing. Her brow furrowed. She seemed deep in thought. Suddenly she yelled. She dug her shoe into the mud and kicked a clot of mud up onto the side of the road, where it was immediately splattered beneath the wheel of a gray Nissan Sentra.

“It sucks,” I said.

She laughed.

“It fucking sucks,” she said. “Now let’s go get drugs.”

On the way back to the center we stopped in the middle of a suburban street. I didn’t know why until Mara put her finger to her lips and pointed. By the street corner, opposite a rotting Little Free Library, there was a metal blue post box. Every so often the post box would thump— sometimes once, sometimes a few times in succession, like a hospital patient with an irregular heartbeat. Mara hitched her bike to a tree and carefully picked her way over to it, rolling the balls of her feet against the ground the way I’d seen my dad do the few times we’d gone hunting. She lifted the metal flap of the post box and shrieked.

I sprinted over immediately. Mara was holding her hands to her face. Her eyes were wide. It was rare that anything frightened her. I was accustomed to being the one in need of protection.

“There’s a bat,” she said.

“A what?”

“A bat,” she repeated. “In the post box.”

I knelt by the side of the box and put my ear to the warm metal of its frame. Inside I could hear the scratch and flap of wings, a sound that might have been chirping. I lifted the flap and looked inside. Something velvet brushed my hand and I let it drop, stifling a curse. It took a moment before I was bold enough to open it again. Through the thin slat of light I could see something black and shiny dangling from the ceiling of the box. I tried to remember if bats carried any infectious diseases, but the only condition I could remember anyone contracting from a bat was vampirism. I pushed my arm in to the shoulder and wrapped my fingers around it. It thrashed for a moment and then was still. I could feel the warmth of its body, the strangely slick texture of its wings, the hummingbird-patter of its little heart. If I closed my fist I could have split its ribcage. I felt queasy. I pulled as delicately as I could, dislodging its grip from its perch.

As soon as it had passed the lip of the box the thing writhed in my hand and took off. It made uneven, spiraling loops in the air as it rose. It looked strange framed against the blue of the sky, an alien beneath the sun. After a moment it veered right, darting amidst a clump of trees and disappearing.

“That was bizarre,” I said.

“Yeah. How do you think it even got there?”

“I dunno. Box got wedged open somehow, and then stuck closed again?”

“Cooking in a metal cage like that,” Mara said. “Poor thing.”

I rubbed my thumb against the center of my palm. It was greasy where the bat had touched me, slick with some oil secreted from its body. I didn’t feel dirtied as much as marked; picked out for something I couldn’t imagine. Where did bats go during the daytime? I didn’t know, but I hoped it made its way back regardless.

“It’s getting hotter,” I said. “I read online that it's messing with animals’ normal behaviors.”

“I don’t think I could bear it much hotter than this,” Mara said.

Suddenly I felt as if I were on the verge of thinking something terrible. There was some connection I hadn’t yet made, and I was certain it would destroy me but I searched for it anyway. I balled my hands into my fists and pressed my nails into the meat of my palm until I drew blood.

Later I waited while Mara picked up the weed, sticking my hands in my pockets and doing my best not to look like a narc. I was waiting in front of some red brick building that’d been empty longer than I’d been alive. By the path that lead to the door there was a metal plaque reading Constructed in 1913, this building was the first and then some other things I couldn’t be bothered to care about. Maybe it mattered to the ghost, though.

Or maybe, I thought, I had been thinking about ghosts all wrong. Maybe a ghost could be something cast by the future, instead of just the past. Maybe everything had already happened on some fourth-dimensional register, and we were just locked to the rails like we were riding through It’s A Small World. Maybe there were things that could descend out of the future to reach you, events so monumental they spilled out over time to presage themselves. Maybe we were always surrounded by ghosts and would never know it. In horror movies, people always understood the omens at the exact moment it was too late for them to help. When Mara came back, an eighth secreted in the pockets of her hoodie, I thought about telling her what I had felt. But I saw her smile, and I heard her laugh as she asked me what was wrong, and I couldn’t bring myself to say anything.

“This whole town’s going to be underwater someday,” she said. We were biking slow, close enough to hear each other. The sun was dead ahead. The golden afternoon light oozed through heavy air. We were suffused by it. I felt as if we were riding across the surface of a distant planet. The street was empty, and in the moment I could pretend we were the only two human beings that existed.

“Says who?”

“Gavin.”

“Who’s Gavin?”

Mara took a hand off her handlebars and patted the pocket where she had stashed the eighth. The glittery tassels on the bars fluttered in the wind. “Gavin. He says global warming is going to drown us all.”

“Oh,” I said. Then: “I wouldn’t mind seeing this place underwater.”

Her grin was wicked. “Me neither. A big ol’ flood washing everything away. He says it’s probably not going to be until we’re like. Eighty, though.”

“That’s too bad.”

I closed my eyes and listened to the sound of Mara pulling ahead. I thought about a huge storm coming, a tsunami like you saw in the disaster movies. I thought about what my house would look like ripped up from its foundations. I thought about torrents of water slaloming down the halls of our school, washing everyone away: Juniper Holzer and Christine Vernon and Luis Rios and Ms. Czernowitz (whose first name was Dolores) and Rory Vartanian and Mara all floating off, carried by the currents into another life. I thought about the darkness at the bottom of the ocean. I thought about the cold. I thought about what it would feel like to drown.

I opened my eyes and she had pulled far ahead of me. I watched her silhouette framed against the sun. Suddenly I felt terribly sick. I struggled desperately to keep up.

“Hey, let’s stop here.”

Near the wetlands the town broke away into patches of thin forest. There weren’t too many ticks, and the tree-line provided a degree of cover from the main road, so it was a good place to come if you didn’t want to be seen. I heard some rumors from kids in my grade that upperclassmen called it ‘Fuck Forest’, and came out here to have sex without people noticing, but I didn’t really believe them. For my part I couldn’t imagine ever having sex with anyone. It was something for other people.

We crossed a ways into the wood before setting up at the base of an old gnarled oak, studded with knurled growths like tumors and spots where kids had carved their names with penknives. The grass beneath was clustered with an invasion of dandelions in full bloom, like someone had draped a yellow carpet over the grass. Mara fished one of the flowers out of her ziplock baggie and set about tearing it into little pieces with her fingernails. The pipe was purple and ceramic and reminded me of Fry’s holophonor from Futurama. I liked to watch her work. While she picked apart the flower an expression came over her face like she was meditating, or solving a complex math equation in her head. She seemed perfectly aligned with herself, every cell in her body in coordination. After a while she handed me the pipe and a lighter and I took a long hit. I didn’t manage to keep from coughing.

“Lightweight.”

I sputtered between wheezes. “Fuck you!”

“You wish.”

The pipe traveled back and forth a few more times. By the time the bowl was empty we were lazy and absurd. I lay prone against the grass, flexing my hands, reveling in the feeling of the damp earth beneath my fingers. Mara sat with her back against the tree, stretching a hair tie between her forefingers and thumb.

“Hey,” she said. “Come here for a second.”

I raised myself up on one arm. “Why?”

“Just c’mere,” she said. “Don’t you trust me?”

I almost resented her for asking. I crawled up to her and she took my head in her hands, positioning me over her lap. Gently she began to pluck dandelions from the grass and weave them between the strands of my hair. When her fingers touched my scalp I stopped breathing for a moment. I couldn’t think. Her touch was the only thing that existed in our private universe.

“Your hair is so soft,” she said. “It’s pretty unusual.” I counted the patches of sky framed between the eaves of the trees. I could feel the steady beat of Mara’s heart through the artery in her thighs.

“Most boys just use any old shit,” she said. “Shampoo/conditioner/body-wash hybrid. Hair like papier-mâché helmets. Bathe twice a week, drench themselves in fucking Axe and Old Spice before they go to school. They’re obnoxious.”

“I’m a boy,” I said.

“Whatever,” she said. “I obviously didn’t mean you. You’re different.’

I didn’t say anything. I felt a pulse of light erupt somewhere deep within my body. I felt warm all over, saturated. Her fingers moved through my hair, leaving behind flowers.

In that moment I was struck with the conviction that if I remained perfectly still time would pass me by. If I held exactly where I was, this would never have to end. I wanted nothing more than us, here, preserved in amber for the rest of existence. I wanted to stretch this moment out into timelike infinity. I felt her hands, her heartbeat, the warmth of her body. I thought: I want to kiss her, and at the exact same moment I knew that thought wasn’t right. The thought was only the nearest approximation to what I actually wanted to do, which was an action for which no words existed. And then I moved, and the moment was over.

The land sloped down to the sea, and we followed. After a while the road turned too rocky to ride. We walked our bikes from there on out. We followed the path further out as it zigzagged and curved to accommodate grasping tendrils of silvery water that penetrated deep into the coast. A procession of ducks floated past, briefly obscured by a clump of reeds. The water was still enough to form a perfect mirror of the sky, and each bird was accompanied by an inverted double hanging below them.

The sun was ponderously low in the sky. We held our hands out to shield from the light. I watched as it crawled into the ocean: first scraping the edge of the horizon, then kissing it. There was some haze over the water. The air bent and shivered.

Someone had installed a metal-frame bench overlooking the sea. The memorial plaque screwed into the swollen wooden boards was abraded beyond readability. We sat down, leaning our bikes against the side. I was still high. Everything around me had a slightly muted, unreal feeling. I felt as if I were watching my own actions on a screen. I fixed my eyes on the horizon and waited for something to happen.

We waited, neither of us speaking. After a little while my eyes begin to water. The sea cut slices from the sun. I began to move to leave when I felt Mara’s hand on my shoulder.

She pointed. Against the horizon something had emerged. Two black blotches wavered in the heat. Another few moments and they had gained substance, until they began to resemble the silhouettes of human beings. They slid across the water towards us, the surface undisturbed by their passage. A hundred heartbeats later I had recognized who they were.

“They look like us,” Mara whispered. Her voice only confirmed my own certainty. It was strange: I could barely see them, and yet I felt utterly certain that they were ourselves, or something resembling ourselves. I recognized them by a means other than sight.

The joints of my body were locked solid. I felt like an insect someone had pinned to a display board. There was something different about the second shadow, the one who seemed like me. I couldn’t figure out what it was.

“They’re coming to tell us something,” Mara said. I knew she was right. I didn’t want to hear whatever they had to say.

The forms of the silhouettes seemed to ripple and flow outward as they moved, so that it was less that they walked and more that they endlessly divulged themselves across the surface of the water. Their borders rippled. I thought: nothing survives what’s coming unchanged.

As they drew closer the figures seemed to take on substance, as if they were feeding off the shadows that drooled from every stone and every tree. I glanced at Mara. She was wide-eyed and rigid. I took her hand and squeezed it as hard as I could. I felt witness to something momentous and terrible at once. Everything inside me had fallen silent with their appearance. One of them raised a hand. Their arm warped and shuddered in the haze. Trembling, I raised mine in return.

The instant the last sliver of sun vanished below the horizon the figures dissolved. One moment I could clearly make out their shapes advancing across the water; the next, they had melted into the haze from which they were born. It was as if they were some magic-eye picture whose solution I had forgotten. Over the sea, the dim afterglow died. Darkness poured across the world in full force.

“You saw that too,” Mara said. “Tell me you saw it.”

I couldn’t speak. At that moment I was filled with the certainty that something terrible was about to happen, or had already happened and was merely taking its time on its way to reach me. Dread sunk into me from all sides. I gripped the boards of the bench to keep myself from swooning. I felt as though they were turning off the lights in Heaven. I tried to keep from crying. I failed. I looked up into the sky and the stars danced and shuddered before me. Cool wind brushed the angles of my cheeks. The night was oppressively beautiful.

“Hey,” Mara said. “Hey, what’s wrong?”

I wanted to say: I believe something awful is happening to me, or is happening to the world, and I no longer know how to tell the difference. I wanted to say: I feel as though I am in the process of becoming something altogether alien, that everything in which I once found comfort is becoming strange, that I find myself as foreign and frightening in my own eyes as every other human being. I wanted to say: At every moment I feel subject to some lonely gravity wrenching me away from everything that exists. I wanted to say: I am terrified of waking up one morning and no longer remembering the sound of your voice; terrified of the conviction that everything we have is unstable and impermanent; terrified that you will abandon me or I will destroy you because I do not understand how to be alive. I wanted to say: you are the only person that has ever mattered to me. I wanted to say: your kindness is the closest thing I have ever experienced to the divine. I wanted to say: I am afraid. I wanted to say: I love you.

Instead I said nothing.

After a while, we got on our bikes and headed home.